First off, I would like to say how sad I am for those who have lost their lives to COVID-19, offering my support and empathy to their loved ones. We live in Sonomish County, Washington, not very far from King County and Kirkland. We’ve already seen the devastation which COVID-19 can wreak on care facilities for elderly people. This disease is all too real.

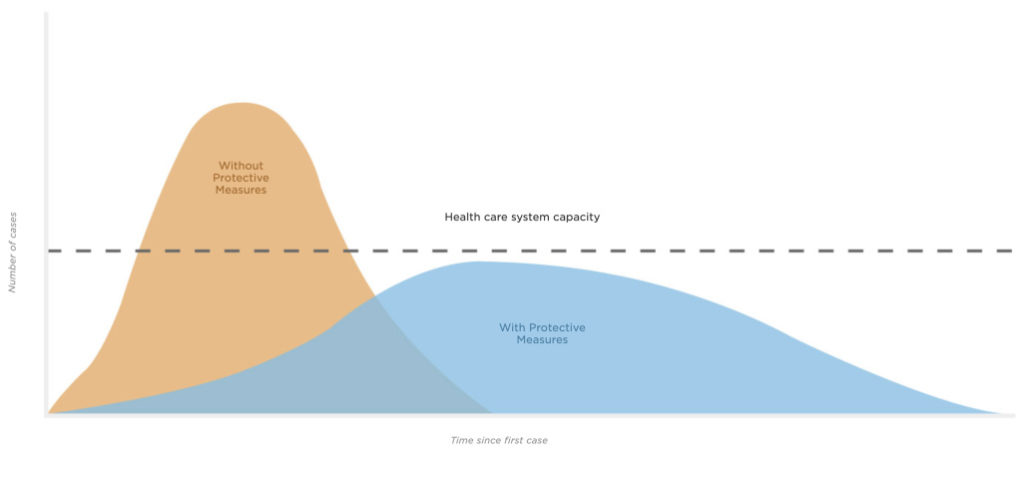

By now, you’ve heard the phrase “flattening the curve” and have probably seen the graph from the CDC (below). Our global goal is to slow the spread of COVID-19 through the population such that severe cases do not overwhelm the health care system. In a nutshell, the health care system has a fixed number of beds, doctors, nurses, caretakers, respirator, ventilators, etc. When capacity is exhausted, the system cannot treat all incoming patients (COVID-19 plus the regular, on-going stream of emergency situations like heart attacks, strokes, etc.) and, quite frankly, people will die.

Source: CDC, Drew Harris (Connie Hanzhang Jin/NPR)

The graph has done a good job of educating us as to the need for social distancing, hygiene, and other measures which slow the spread of disease.

It also suggests a metric — a key performance indicator (KPI) — which can tell us how well we are doing. A KPI is a measurable value that demonstrates how effectively an organization is achieving its objective(s). It’s important to note that a KPI can and should be applied at different levels in the organization. We also need to know how the KPI changes over time.

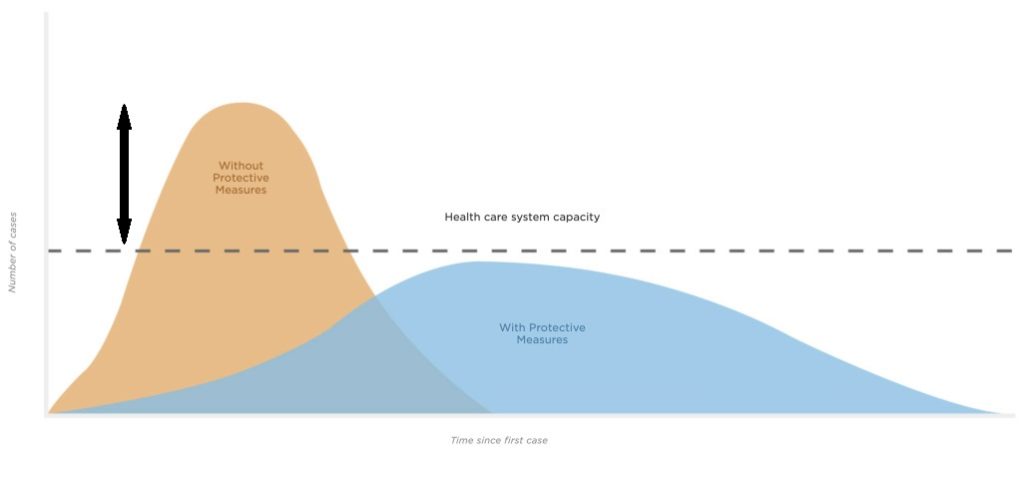

Let’s consider a KPI which measures the number of all critical care patients above or below the capacity of the health care system (below). This delta tells us if we are successfully suppressing the spread of COVID-19 or not. We must measure all critical care patients because they all are vying for the same medical personnel, beds and equipment. If the KPI is positive, i.e., the number of critical care cases exceeds capacity, then we are failing. If the KPI is negative, then we are succeeding.

A national KPI value is only somewhat useful. The KPI needs to be measured at the state level and regional (metro) level. State-level values are useful only for small states such as Rhode Island with one major population center. Regional-level values are more useful in large states like California or Washington with two or more major population (and health care) centers. The U.S. is a very large country and health care capacity in West Virginia, for example, is not available to residents in San Francisco. Thus, regional numerical break out is required.

We need to track the KPI over time. The trend will tell us if we are successfully supressing the spread of COVID-19 or not. Tracking by region over time will tell us if hot spots are cooling off or if new hot spots are developing.

Why am I proposing this KPI, especially now? As a people, we need to walk a fine line between actionable concern and fearful panic.

I see tables and graphics in the media which tally the total number of confirmed cases and the total number of deaths. Yes, we mourn the loss of our neighbors. If we have even an ounce of humanity, can we not? I agree that such figures convey the sense of urgency needed to motivate new behavior that slows the spread of disease.

However, the total number of confirmed cases and fatalities alone are flawed measures for decision making. With respect to confirmed cases, the number can only go up — drastically — as we ramp up testing. Media need to at least report the number of people tested each day along with the number of negative results as well as the number of new confirmed cases. Even then, perhaps only the ratio of new confirmed cases to the number of new tests is truly meaningful.

Just to be clear, “each day” means the number of people tested, confirmed positive and negative in a specific 24 hour period, not an accumulated tally to date.

Aggregated and accumulated measurements are not practical and may be unnecessarily misleading. News media please take notice.

We also need to break out and track new critical COVID-19 cases which require hospitalization. These are the people who need the health care system. By tracking this number, we will see if the load on the health care system is trending upward toward catastrophe or trending downward successfully. As much as I love my younger and/or healthier brothers and sisters, if they are successfully recovering in self-isolation, then they are not loading the health care system with negative implications, and possibly death, for critical care patients.

I apologize to anyone who may feel offended by my frank discusion. I’m trying to come to grips with all of the information thrown at me by media outlets. Hopefully, you will find this approach to be useful. Even if you do not adopt my proposal, I hope to have started a practical discussion.

Wishing you safe passage — P.J. Drongowski