After having so much fun last year, I couldn’t pass up the 2018 Boston Music Expo (Saturday, June 9). Music Expo brings people together — artists, producers, engineers, composers, tech companies — the whole panoply of folks at the intersection of musical art and technology.

Sound On Sound Magazine is the chief sponsor. This year’s gold sponsors are Yamaha and Steinberg. Of course, both Steinberg and Yamaha were showing their wares along with many other companies big and small.

Loïc Maestracci — the founder of Music Expo — was at the door with the chance for a quick “Hello!” Let’s get started and go in.

Boston Music Expo 2018 was hosted by The Record Co., located in Boston’s South Bay. The Record Co. has the ambitious mission “to build a sustainable, equitable music scene in Boston.” Although Boston already has a busy scene, it isn’t easy for all artists to grow, collaborate and record. The Record Co. provides subsidized studio space, gear and production resources, thereby lowering the financial barrier for artists looking to record.

The Record Co. has two studios, both kitted out with top-notch gear. Rates are very reasonable. The Studio A live room is quite large and was the venue for one of the two parallel seminar tracks running at Music Expo. Studio A held 40 to 50 seats with space to spare. Studio B is smaller and more intimate.

The thing that I like best about Music Expo is the surprises. While getting my bearings, I was blown away to find people soldering! I had stumbled into the Audio Builders Workshop sponsored by the Boston Chapter of the Audio Engineering Society (AES).

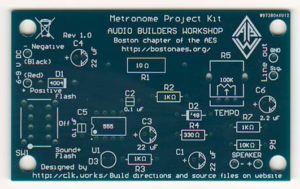

The Audio Builders Workshop offers seminars and group builds to encourage and inspire people to make their own audio electronics. I had a great chat with Brewster LaMacchia (Clockworks Signal Processing) who was leading the group build. The workshop participants were building a small metronome kit ($10 donation). The kit consists of a circuit board, 555 timer, speaker, battery connector, and a handful of discrete components. It’s all through-hole construction and looks like a great way to get started with soldering. If you’re in the Boston area and have an interest in audio electronics, then I definitely recommend getting in touch with this organization.

I bought one of the kits and will eventually build and review it. Sometimes I just like to soldering something up on a rainy day.

Another organization at Music Expo that deserves recognition and support is Beats By Girlz. BBG is a “music technology curriculum, collective, and community template designed to empower females to engage with music technology.” BBG sponsors workshops and other events (hardware and software provided!) to get women and girls into music production, composition and engineering.

That last “E” for “engineering” gets me fired up! Music technology, for me, is the gateway drug to Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) education and careers. Women are so woefully underrepresented in STEM that I wholeheartedly support groups like Beats By Girlz. In addition to Boston, BBG has chapters in Minnesota, Los Angeles, New York and Chicago. I recommend Women In Music, too, BTW.

I arrived at Music Expo a little later than expected due to a traffic tie-up on the expressway. (Saturday morning? Really?) However, I did manage to catch the two sessions in which I was most interested.

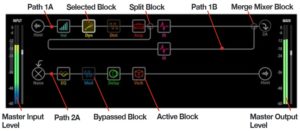

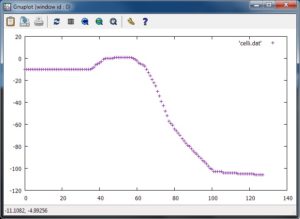

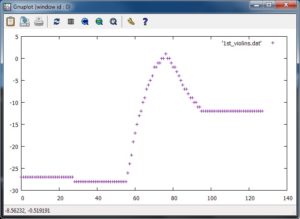

Since it was first announced, I wanted to see and hear Audionamix Xtrax STEMS in action. I’ve tried to spice up my backing tracks with vocal snippets and found center extract (and center cancel) techniques lacking. My first “must-hear” session at Music Expo was an Xtrax STEMS plus Ableton Live presentation by Venomisto. Venomisto used Xtrac STEMS to pull a vocal stem from an existing song and then inserted the vocals into his own remix. Xtrax STEMS is not perfect, but it’s darned good for the money ($99 USD).

I really dug Venomisto’s latin remix, Havana. Toe tappin’, head noddin’. I love this stuff on a Saturday in the city! [I’m listening to it right now and can’t get back to work.] Cruise over to his site and you’ll hear Xtrax STEMS in action, too.

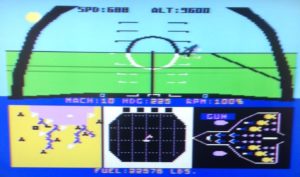

My second “don’t miss” session was “From Score To Stage” by Paul Lipscomb joined by Pieter Schlosser via Skype. Paul ran through the process of sketching and delivering the “Destiny 2” game soundtrack (Bungie Software). Wow, this session could have been a full day.

Although Paul wanted to show people that there are many ways to work and create as an artist, we’re talking “Production” here with a capital “P”. The Destiny 2 soundtrack is a AAA (big) budget production with multiple composers, orchestrators and an orchestra. All I can say, if you want to do this kind of work, be good at the hang and collaboration. Be prepared to work in a geographically dispersed team: client (Bellevue/Seattle), co-writers (Los Angeles, Seattle), orchestrator (The Berkshires in Massachusetts).

Paul classifies music (and the process of getting there) as either linear or interactive. Music for film or video is linear, having a start point, several intermediate points one after another and an end. Game music is interactive and must adapt and re-structure itself to fit the actions of the player.

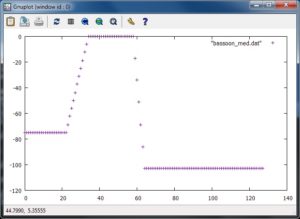

He demonstrated how one can start with a simple motif (or two) and build your way to a 250 track behemoth. Thanks to the wonderful orchestral libraries available today, composers can put together a rather complete mock-up to present to a client for approval. Even on a big budget job, some of the parts in the mock-up may make it to the final mix simply because there isn’t enough money available to fund everything live (e.g., you can have the orchestra, but not the choir).

Paul uses Steinberg Nuendo and swears by it. Pieter uses Cubase. Nuendo is the bigger brother to Cubase and is geared for post-production and scoring. Paul exports MIDI tracks and provides them to the orchestrator for notation. Yep, good old MIDI.

Paul and Pieter’s presentation was thought provoking, especially about the current state/direction of orchestral music for film, video and games. A discussion about clients and aesthetics would be more appropriate for the “Notes From The Deadline” column in Sound On Sound. [My favorite SOS column, BTW.] However, I’m pondering the age-old question of how to raise our clients to a higher level of musicality. Like Paul, many of us listen to a wide range of music including traditional and modern classical music. (Paul’s advice: “Listen to everything!”) How can we move our clients beyond the limited scope of their own musical experience?

Well, shucks, that’s just two of the fifteen Boston Music Expo sessions on offer. Several sessions dealt with the business side — promotion, social media and collaboration — in addition to the artistic side.

I spent time cruising the exhibitor booths. Here’s a few short-takes and shout-outs:

- Scott Esterson at Audionamix demonstrated Instant Dialog Cleaner (IDC) as well as XTrax STEMS. He humored a lot of my crazy questions and comments. Thanks.

- The Yamaha folks had Montage6, MX88, MOXF8 and a clutch of Reface keyboards available for trial. Friendly as ever, it was good to touch base. I had an extended conversation with Nithin Cherian (Product Marketing Manager, Steinberg) and I quite appreciate the time that he spent talking with me.

- The IK Multimedia iLoud Micro Monitors are excellent for the price. Not quite up to the Genelec studio monitors on show in the room next door, but much more affordable. A definite covet.

- Speaking of IK, the iRig Keys I/O have a decent, solid feel and touch. The 25 key model is seriously small and still has full size keys. Suggestion to IK Multimedia: Please bring out a 5-pin MIDI dongle for us dinosaurs with old keyboards. I’d love to hook up an iRig Keys I/O 49 to Yamaha Reface YC.

A special shout-out to Derrick Floyd at the IK Multimedia booth. He epitomizes “good at the hang.”

I said it last year and I’ll say it again, Music Expo bridges the widening gap between customers and technically advanced products. On-line ads and videos just aren’t the same as playing with a product and experiencing it for one’s self. Brick and mortar stores cannot devote much space, inventory or expertise to the broad range of fun tools and toys that are up for sale. With on-line sales as perhaps the dominant sales channel, whoof, tactile customer experience is utterly lost. Music Expo closes the gap.

If Music Expo is coming to your corner of timespace, please don’t hesitate to attend and participate. I’m sure that you will enjoy the experience and will make valuable connections.

Copyright © 2018 Paul J. Drongowski