I’m happy to write what may be the first end-user review of the Roland GO:KEYS.

The GO:KEYS is one of two new entry-level keyboards from Roland. The GO:KEYS has a street price (MAP) of $299 USD and is intended to inspire new keyboard players without a big out-of-pocket outlay.

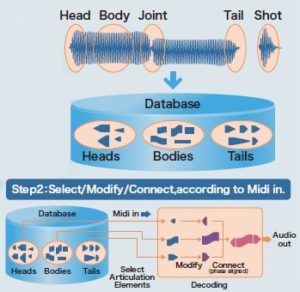

The hook is the five zone, Loop Mix mode. The 61 keys are separated into 5 one octave zones: Drum, Bass, Part A, Part B and Part X. Each key in a zone triggers a two measure musical loop that repeats until the zone-specific STOP key is struck. The Drum and Bass zone lay down the basic groove while Part A and Part B add the harmonic bread and butter, like electric piano comping or a string pad. Part X adds variation with up to four phrase subgroups. Only one phrase can play in a zone at a time.

The preceding paragraph takes more time to read than it takes to set up a backing track. When you have the band grooving, you can switch to regular keyboard mode and solo to your heart’s content. Whenever you feel like it, you can switch back to Loop Mix mode and move the band to a different place.

There are twelve different Loop Mix Sets. Each set is a scale-compatible collection of Loop Mix phrases. The twelve style names suggest the musical genres and the target audience for GO:KEYS. No polkas. The Sets are modern sounding, however, I can’t speak to the authenticity of the EDM styles. The FUNK set sounds more like funky smooth jazz — no JB, no George Clinton, here.

However, don’t let that stop you. Please watch the GO:KEYS videos that Roland has posted on Youtube. (Search “Roland GO:KEYS”.) You’ll quickly decide if the GO:KEYS is for you or not. I certainly have had a lot of fun jamming away.

Many aspects of the GO:KEYS are well-thought out. It’s clear that the developers tried to play their own creation and added a number of convenience features like using the touch strip to step through the Function menu. The GO:KEYS can remember previous settings across power-off and it remembers the last patch selected in each of the eight categories (piano, organ, strings, brass, drum, bass, synth and FX/guitar).

Recording and playback are fairly rudimentary. Don’t expect a workstation at this price point! You can record an improvised backing and save it to a song file. Thanks to USB, the song file, etc. can be saved to a PC or Mac through the back-up function. The PC or Mac treat the GO:KEYS like a flash drive. You copy the back-up folder to the PC/Mac and you’re done. The directions in the user manual are simple and accurate, so I won’t go into those details here.

Windows 7 recognized the GO:KEYS when I plugged it in. Windows installed the Microsoft generic USB audio driver. Windows didn’t try to install the flash driver until I attempted the first back-up. The driver installation at first appeared to fail. When I unplugged and replugged the GO:KEYS, everything was fine and the GO:KEYS drive appeared in Windows Explorer.

My GO:KEYS arrived with version 1.04 of its software installed. There is a version 1.05 update on the Roland support site. Roland’s on-line directions are simple and accurate. The update to 1.05 went smooth.

The GO:KEYS sound set is a real bright spot. The standard “panel” voices are taken from the successful JUNO-DS series. In fact, I auditioned these voices by trying them out on a JUNO-DS88 before ordering the GO:KEYS. The GO:KEYS voices sound very similar, especially when you send the GO:KEYS through decent monitors. The built-in speakers are OK, but again, don’t expect super high quality in an inexpensive keyboard. The GO:KEYS is perfectly respectable through the Mackie MR5 mk3 monitors on my desktop.

Here are the sonic highlights:

- The electric pianos are really strong. Many voices have tasty, appropriate effects (e.g., phaser) applied. If you need acoustic piano, try GO:PIANO instead.

- There are a slew of synth leads and basses. I’m in love with Spooky Lead which is a classic fusion, R&B tone.

- Organs are typically Roland — OK, but not tachycardia-inducing.

- The strings are also typically Roland — darned good.

- Acoustic sounds — few as they are — are decent. I like Soft Tb and Ambi Tp. Other acoustic sounds may be found in the GM2 sound set. (Don’t forget to enable them in the settings!) The woodwinds are surprisingly good for GM2.

I haven’t dug too deeply into the rest, but the voices triggered by the phrases sound good and are well-chosen. Clearly, the JUNO-DS is the original source.

At this price level, the GO:KEYS is a preset-only machine — no voice editing. The most you get is the ability to set the reverb level. Even the reverb type is fixed (a nice hall). There are decent multi-effects under the hood as heard in the electric piano and clavinet voices. Alas, everything is preset and fixed. Roland would still like to sell you a JUNO-DS.

The GO:KEYS includes a full General MIDI 2 (GM2) sound set. It sounds like an improved set over the much older RD-300GX for which I have produced many GM2 Standard MIDI Files (SMF). I have not tested GM2 compatibility. Roland are very careful about this and have not advertised full compatibility. This is not much of an issue for me as I have plenty of sequencing resources on hand already.

The GO:KEYS does not have conventional pitch bend or modulation wheels. The touch panel has two strips that apply pitch bend or filter/roll effects. The adjacent FUNC button selects the mode. The filter and roll are applied to everything, so you get a DJ-like effect that rolls the rhythm or squishes frequencies. Pitch bend mode also seems to include modulation. I hear the rotary speaker change speed on some organ voices. Unfortunately, attempts to change rotary speed also bend the pitch.

Hey, Roland! I regard this behavior as a bug. The documentation is really loose about what these touch strips do. In the next update, please make one strip pitch bend only and make the other strip modulation only. Punters everywhere will thank you!

The GO:KEYS is very light weight coming in under nine pounds. Power is supplied by either the included adapter (5.9V, 2A) or six AA batteries. The voltage rating is a little odd, 5.9V. I wonder if it’s OK to use a more common 6V adapter provided that the current rating is sufficient?

The GO:KEYS has two slots to accomodate a music rest, but doesn’t come with a music rest. The GO:PIANO bundle includes a music rest, not the GOKEYS. I want to use the GO:KEYS at rehearsals and will call Roland to see if I can buy a music rest. Of course, the Yamaha music rests that I have on hand do not fit the slots and cannot be easily adapted. (Arg. Put the Dremel tool away.)

As you might think, the keybed is not super stellar at $299 street. The keys are piano size and shape with a nice texturing (not plastic-y smooth). The keys don’t feel too bad although it’s more difficult to palm swipe piano-shaped keys with an edge.

Key response is OK, but not as good as a more expensive instrument. (Full disclosure, I played a $3,000 Yamaha Montage last night.) One key is a little dead and its response is quirky. I’ve encountered the same problem with a single key on the otherwise superb Arturia Keystep, too. It’s hard to make a keyboard at this price point that provides high quality and reliability. Even though the GO:KEYS’ case feels sturdy, I wouldn’t gig this machine too hard. You get what you pay for.

Overall, I’m pleased with the GO:KEYS. It’s a good starter keyboard and it looks (and sounds) to be a decent portable rehearsal instrument. The GO:KEYS is an attractive alternative to Yamaha and Casio products in the same price bracket. Definitely worth a look and a listen.

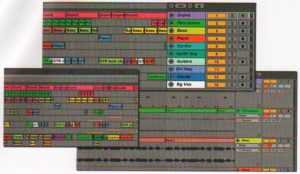

Update: After writing this review, I sequenced a GO:KEYS demo track in Ableton Live. The defective key became worse and I returned the GO:KEYS. Please read about my experience and listen to the demo track.

Copyright © 2017 Paul J. Drongowski