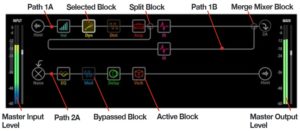

Yamaha Mobile Music Sequencer (MMS) is an app that doesn’t seem to get as much love as it deserves. MMS is a rather complete MIDI sequencing tool to create new songs using a phrase-based approach. (Cost: $15.99USD) The MMS user interface has a superficial resemblance to Ableton Live. It has a phrase screen which lets you assemble preset or user phrases into song sections, e.g., phrases that play as a group. Once you have one or more song sections, you then assemble the sections in the linear song screen. You may also create new phrases of your own in a piano roll editor/recorder and you may record solos and such directly into a song track.

MMS includes an XG-architecture sound engine although the voice set is limited to a General MIDI (GM) subset and a collection of MMS-only voices. Voice quality is “just OK” and may be why MMS adoption is slow. However, as I’ve recently discovered, there are a few hidden gems like a Mega Voice clean electric guitar! DSP effects are basic and follow the XG effects architecture. I have summarized the sound set, DSP effects, etc. on my Mobile Music Sequencer Reference page.

Of course, you can mixdown and export full audio songs from MMS. MMS supports SoundCloud, Dropbox, and iTunes file transfer. You can also export a song to a Standard MIDI File (SMF). The SMF has eight parts — one part for each of MMS’s eight song tracks. If you choose one of the supported targets (Tyros 5, Motif XF, MOX, etc.), MMS inserts bank select and program change MIDI events to select an appropriate voice for each track. Unfortunately, MMS doesn’t export volume, pan or effect data, so the resulting SMF is quite naked. Ooops! This is one area where MMS could be and should be drastically improved.

MMS’s voicing for Tyros is not very adventurous. On the up side, SMFs targeted for Tyros should work quite well on other PSRs, too. There is one voicing issue which should be fixed. The MMS clean electric Mega Voice (“Clean Guitar 2”) should be mapped to the good old PSR/Tyros clean guitar mega voice. Right now, it’s mapped to the regular clean guitar voice and the guitar FX sounds are whack.

Yamaha have rather quietly enhanced MMS’s capabilities. MMS is now up to version 3, including chord templates, extraction of chord progressions a la Chord Tracker, and more. The last minor update made MMS compatibile with Apple iOS 11. I hope Yamaha add Genos and Montage support because MMS can communicate directly (via wired MIDI, Bluetooth MIDI or wireless LAN) to its supported synths and arrangers.

Given the amount of kvetching about the shortcomings of the Montage sequencer, I’m surprised that more Montage people haven’t picked up MMS. Same for Genos or PSR, for that matter. Maybe its the lack of direct Montage or Genos support?

Where you from, boy?

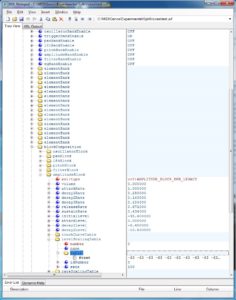

Recently, I got the itch to create a few new PSR-compatible styles. I’ve always felt that MMS would make a good base for a style editor. You can quickly slam together phrases into a song section and see if they play well together. (Same as Ableton Live, I might say.) I mix and match phrases into song sections then export the sections to an SMF. Each MMS song section is a PSR style section (MAIN A, MAIN B, etc.) I load the SMF into a DAW where I add style section markers, SysEx set-up data, volume, pan, etc. When satisfied, I add a style CASM section using Jørgen Sørensen’s CASM editor. [Be sure to check out all of Jørgen’s excellent tools.]

Given the content, I can just about do this in my sleep. It’s a fairly mechanical process once you understand it and do it, say, fifty times. 🙂

About that content…

MMS comes with ten styles (i.e., groups of phrases) in the initial download. Please see the table at the end of this article. The ten styles are rock and pop. If you’re looking for R&B, dance, jazz, electronic or hip-hop, you’ll want to buy one of the content packs offered as an in-app purchase. I’ve include a table for these packs, too, at the end of the article. The genre packs are $3.99USD each. Yamaha also offer the multi-genre QY pack ($7.99USD) with phrases taken from the Yamaha QY-70 (QY-100) handheld sequencer. I did a little QY-70 mining myself.

Now for the usual Yamaha archeology…

The “MM” in “MMS” is a little bit ironic. The MMS phrases are lifted from the (infamous) “Mini Mo” mm6 and mm8 keyboards. The Mini Mo touted voices taken from the Motif series, but the mm6 and mm8 didn’t really know if they wanted to be an arranger or a synthesizer. In that regard, the Mini Mo is a unique functional hybrid in Yamaha’s bipolar world. (“You’re either a synth or you’re an arranger.” Digital pianos excepted, of course.)

So, yep, MMS offers almost all of that old (ca. 2006) Mini Mo goodness. You don’t get the fun ethnic patterns (Turkish, African, Indian), tho’.

If you break into your rich neighbor’s house to steal his stereo, you might as well take the TV set, too. The Mini Mo arpeggios are incorporated into the the Yamaha Synth Arp & Drum Pad app. If you still can get the Synth Arp & Drum Pad app, snag it right away. It’s being discontinued.

How does it sound on Genos?

Not bad. Even though the target voices are rather vanilla, an MMS-derived style on Genos sounds pretty darned good.

List of MMS drum kits

| Bank MSB | Bank LSB | Prog# | PC# | Drum kit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7FH | 00H | 1 | 00H | Standard Kit |

| 7FH | 00H | 26 | 19H | Analog T8 Kit |

| 7FH | 00H | 27 | 1AH | Analog T9 Kit |

| 7FH | 00H | 28 | 1BH | Dance Kit |

| 7FH | 00H | 41 | 28H | Brush Kit |

| 7FH | 00H | 84 | 53H | Break Kit |

| 7FH | 00H | 85 | 54H | Hip Hop Kit 1 |

| 7FH | 00H | XX | xxH | Hip Hop Kit 2 (Hip Hop) |

| 7FH | 00H | XX | xxH | Hip Hop Kit 3 (Hip Hop) |

| 7FH | 00H | 88 | 57H | R&B Kit 1 (R&B) |

| 7FH | 00H | 89 | 58H | R&B Kit 2 (R&B) |

| 3FH | 20H | 1 | 00H | SFX Kit |

| 3FH | 20H | 2 | 01H | Percussion Kit |

| 7FH | 00H | XX | xxH | Dubstep Kit (Electronic) |

| 7FH | 00H | XX | xxH | Elct.Dub Kit 1 (Electronic) |

| 7FH | 00H | XX | xxH | Elct.Dub Kit 2 (Dance) |

| 7FH | 00H | XX | xxH | Epic FX (Electronic) |

| 7FH | 00H | XX | xxH | Gate Drum Kit (Electronic) |

| 7FH | 00H | XX | xxH | Short FX (Electronic) |

| 7FH | 00H | XX | xxH | New Pop Kit (Dance) |

| 7FH | 00H | XX | xxH | Trance FX Menu (Dance) |

| 7FH | 00H | XX | xxH | Trance Power Kit (Dance) |

List of styles

The following preset styles are installed with Yamaha Mobile Music Sequencer when you buy MMS.

| Category: Rock/Pop | Jazz/World |

|---|---|

| BluesRck | Funky Jaz |

| ChartPop | JzGroove |

| ChartRck | Reggae |

| FunkPpRk | |

| HardRock | |

| PianoBld | |

| PowerRck | |

| RkShffle | |

| RockPop | |

| RootRock |

Here are the styles included in each optional, in-app purchase pack:

| R&B | Electronic | Dance | HipHop |

|---|---|---|---|

| IzzleRB | Ambient | Dncehall | AcidJazz |

| JazzyRnB | Analog | Dncfloor | Amb Rap |

| RB Chrt1 | Chillout | E-Disco | ButiqHH |

| RB Chrt2 | Dubstep | E-DubPop | EastRap |

| RnB Bld1 | ElctDub | EleDance | HipHopPp |

| RnB Bld2 | Electron | ElktPop1 | JazRemix |

| RnB Pop1 | Minimal | ElktPop2 | SouthRap |

| RnB Pop2 | Techno | FunkyHse | WestRap |

| RnB Soul | Undrgrnd | LatinJaz | |

| M-Trance |

Copyright © 2018 Paul J. Drongowski