Sample Robot for Montage (SRM) is a very useful addition to the Yamaha MODX (Montage) product ecosystem. After my initial start-up experience:

I went on to produce two sampled pipe organ voices: Organ Prinzipal and Organ Pleno.

Prinzipal and Pleno

Anyone who sees a pipe organ — especially a cathedral-sized instrument — is immediately impressed by its large array of pipes. The open metal pipes are the principal pipes which give a pipe organ its distinctive sound. Pipes are arranged in ranks, kind of like the individual drawbars on a Hammond B3 organ (vice versa, really!) Hammond-ites know that the length of a pipe determines its pitch and that each rank has a reference pitch (measured in feet) that specifies the rank’s harmonic character when blended with other ranks.

I generally use pipe organ to lead congregational singing. Conventional wisdom for hymn accompaniment is simple: Use principal pipes with simple, foundational pitch: 8′, 4′ and 2′. Although this sounds plain vanilla, the sound is not cluttered by harmonics that may confuse the congregational ear. This kind of organ registration is often called a “principal chorus.” Due to the deep history of pipe organ in Western Europe, a French, German or Italian name may be used instead, e.g., “Prinzipal.”

Old school players understood the need to built energy and drama during a tune, too. Thus, an organist might add non-fundamental harmonics during the final verse and chorus. Think, Hammand organ “whistle”, 1 3/5′, 1 2/3′, etc. Often, a group of such ranks is brought in, a “mixture.” If the mixture consist of principal pipes, then the resulting registration is called a “full principal chorus.” This registration has many names, too, such as “Organo Pleno” or “Plein Jeu.”

In case you’re wondering, reed stops are rarely used for hymn accompaniment, if ever. Flute pipes are occasionally added for quiet meditative hymns. Principals are the real work horses.

Yamaha Musicsoft offers a terrific PSR expansion pack: Church Organ. Someone put a lot of love and care into this pack! I bought a PSR-S950 based upon the strength of the Church Organ pack. Fortunately, the PSR-S970 version of the pack also loads on Yamaha Genos™ and I’ve been able to take advantage of its sounds for practice and live play.

My goal here is to sample the Organ Prinzipal and Organ Pleno voices on Genos and to use those voices on MODX.

Sample, test, repeat

Sampling with SRM is reasonably straightforward. If you read my previous blog posts, then you already have the general drift. I recommend reading the SRM manual, too.

I liked the sampling strategy and key layout used in the Apple Symphony Orchestra pipe organs and arrived at a planned layout of keybanks:

KB# Low High Center

--- --- ---- ------

1 C-2 C#0 C0

2 D0 E0 D#0

3 F0 G0 F#0

4 G#0 A#0 A0

5 B0 C#1 C1

6 D1 E1 D#1

7 F1 G1 F#1

8 G#1 A#1 A1

9 B1 C#2 C2

10 D2 E2 D#2

11 F2 G2 F#2

12 G#2 A#2 A2

13 B2 C#3 C3

14 D3 E3 D#3

15 F3 G3 F#3

16 G#3 A#3 A3

17 B3 C#4 C4

18 D4 E4 D#4

19 F4 G4 F#4

20 G#4 A#4 A4

21 B4 C#5 C5

22 D5 E5 D#5

23 F5 G8 F#5

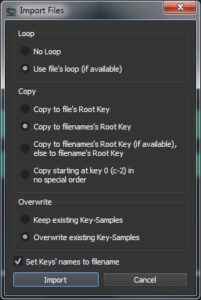

In Sample Robot concepts, this means starting at C0 (MIDI note number 24) and sampling every three semi-tone steps up to C5 (MIDI note number 84). With the exception of the lowest and highest note, a sample is never transposed (pitch shifted) more than a single semi-tone. I also liked the long sample time in the Apple approach and settled on a 12 second capture time plus 0.5 seconds release (12.5 seconds total of capture). I didn’t use the release samples, but I wanted to see and hear them as a learning experience.

If you change the MIDI note range or step number in SRM, be sure to click the Step button! I got hung up and couldn’t figure out why SRM didn’t “see” new note range limits. This really should be mentioned prominently in the SRM manual. I assumed that SRM would simply take what it was given…

These basic sampling parameters can be set using the SRM project wizard. Or, you can set them individually on the various property tabs. I went through the wizard first, then fine tuned individual parameters later.

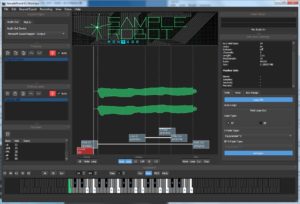

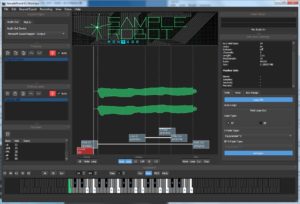

The virtual keyboard at the bottom of the screen shows the notes to be sampled (black and white) and the notes for which samples have been taken (notes with a blue square). The dark grey notes are not sampled. [Click on images to enlarge.]

Before going further, I must state that I made several attempts at sampling each voice. I decided to retain the volume differences (level nuances) across the multisample. I turned Auto-gain OFF and set the audio input level manually. Thanks to the waveform display, I could find any obviously clipped sample. I also did a spot check of questionable samples in Sound Forge Studio. I eventually arrived at a set of samples for each voice in which one (or a few samples) were max’ed and the rest of the samples in the set fell in line as synthesized by Genos. I believe this strategy preserved the natural levels across the pipe organ key range.

Loop quality

I let SRM do the looping. I know from experience that looping pipe organ samples is not easy and is very time consuming. Plus, I wanted to see how well SRM would do.

The Display buttons below the waveform pane control waveform annotations. Enable the Loop button and SRM shows the loop in (start) and loop out (end) points for a sample. I used the default cross-fade loop settings as shown in the screenshot.

SRM’s loops sound decent. There are a few samples where a bit of a surge could be heard, but no obvious bumps or clicks. SRM’s loops are shorter than the Apple loops and that is a little disappointing. However, there aren’t any short cycle loops that lose the dynamic timbral quality of a pipe organ. I think they are all useable as they are without any manual tweaking. My opinion is based upon what I auditioned in SRM and what I heard at the MODX keyboard itself.

Normalization and gain change

Really good thinking went into this part of SRM. SRM gives you several options for normalizing or applying a gain factor across one or all of the samples in a project. (Please see the manual for details.)

Normalization works as expected. It applies a gain factor that brings up the an entire sample such that the peak is 0dB or a custom peak level which you set.

Gain change is just what I needed for this project. I wanted to maintain the relative difference in level between samples — just make everything uniformly louder without introducing clipping distortion. In order to do this, I needed to know the highest dB level for a group of samples then apply a gain factor everywhere to pull all samples up. SRM provides a few different options for finding the overall peak level, e.g., “Find highest dB Level in selected Project”. Suggested improvement to SRM: After analyzing the samples, SRM should display the peak level for each sample in the property pane along with the sample’s other properties.

I like the option “Warn if clipping will occur.” Features like normalization and gain change would make SRM quite useful and necessary even when starting out with old samples borrowed from a VST software instrument. 🙂

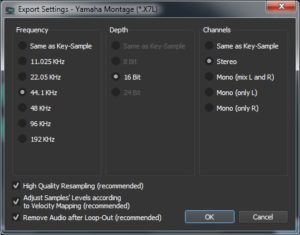

Export and import

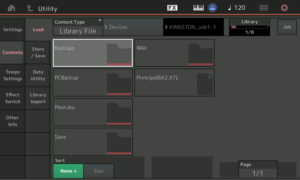

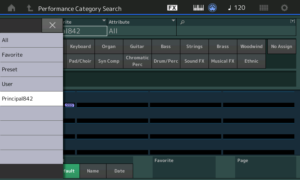

I exported each voice as a Montage LIBRARY file (X7L) and loaded each LIBRARY file into MODX. One nice MODX feature is the ability to audition Performances in a Library. This is a quick way to sanity check new waveforms (and underlying samples) on MODX.

There were several iterations at this stage, too. It took a few iterations to get the desired key range for sampling. The initial key range was one octave too high. I like to have three octaves in the left hand and two octaves in the right hand for hymn accompaniment as I’m faking organ pedals in the left hand. I used MIDI OX to check the high and low MIDI note numbers, then I reset the lower and upper note sampling limits in SRM.

Thankfully, any and all iterations are fast. SRM can sample the entire key range in about 5 to 6 minutes with the chosen capture time for each sample (12.5 seconds). This is welcome and needed time to get a cup and give my ears a rest!

Finishing and sanding

The new waveform needs to be incorporated into a finished MODX Performance because the SRM-generated Performance in the Library file is very, very basic. (Actually basic is a good thing for quality assurance and auditioning.)

In one of my earlier experiments, I had fashioned a pipe organ Performance (Plein Jeu). I repurposed the Performance even though I had long since blown away the Plein Jeu waveform.

My process has (roughly) the following steps:

- Load the LIBRARY file generated by SRM.

- Audition the generated Performance in the Library.

- Import the generated Performance and its waveform into USER memory.

- Select and edit an existing Performance, hopefully one which is close to the desired result.

- Save the new Performance under a new name.

- Edit the effects or any other Performance Common parameters.

- Edit the Part information within the Performance.

- Edit the elements in the new Performance to use the new waveform.

- Edit the new waveform to change its name (category and subcategory), to extend the lower note limit of the lowest key bank, and to extend the upper note limit of the highest key bank.

- Make any other necessary tweaks to the new waveform.

- Make tweaks to the Element programming or effects.

- Save the new Performance.

Clearly, prior experience with Performance and Part editing is a real plus at this stage. Ramp up slowly! Gain experience. Rome wasn’t built in a day.

OK, get ready for TMI. When you load a library, MODX seems to load incoming waveforms into wave memory on a contingency basis. This is why you can audition new Performance waveforms in a library. You can even make a contingent waveform part of a USER Performance. If you haven’t explicitly imported the Library Performance and its (contingent) waveform from the Library and you delete the Library, kiss the waveform good-bye; it’s deleted, too.

When you’re ready to commit to a new waveform, you must explicitly import the parent Performance and the new waveform within to USER Memory via the Data Utility.

A few comments for the developers

Nice work! Here are a few refinements.

Please add the ability to directly monitor the incoming sample stream. It would greatly aid set up and we can listen for audible clipping distortion when setting levels.

Display the peak level in sample properties. This will make it easy to find samples which are (potentially) clipped.

The Project Datapath in the Preferences dialog does not seem to apply everywhere and it isn’t persistent i.e., it is reset to the path “C\Users\xxx\Documents\SKYLIFE\SampleRobot6\Data.” This file path should be used consistently.

A native English speaker should take a quick pass through the manual, which is already pretty darned good. There are occasional spelling and simple grammatical errors (e.g., possessive versus plural). The same reviewer should check the application for spelling errors; there are misspelled words.

The manual should inform the user to press the Step button after changing the MIDI note limits for sampling.

What’s next?

When I A/B’ed the expansion pack organs against the Apple Symphony Orchestra pipe organ, I had to give the quality edge to Apple. I’ve already snagged another voice from the Symphony Orchestra Jam Pack. At the very least, I’ll use Sample Robot for Montage to change gain, to layout the key banks and to generate a Montage LIBRARY file. It shines at these operations and really speeds up the work.

Copyright © 2018 Paul J. Drongowski