My current light-weight rehearsal instrument is a Yamaha Reface YC. Although I have put the YC to work at many a rehearsal, the Reface YC has three major limitations:

- It’s organ all the way and I can vary tone color only with drawbars.

- The three octave keyboard is maddingly too short and chops either the melody or bass line.

- I can cope with the mini-keys, but really?

Thus, my quest for a light-weight rehearsal rig goes on.

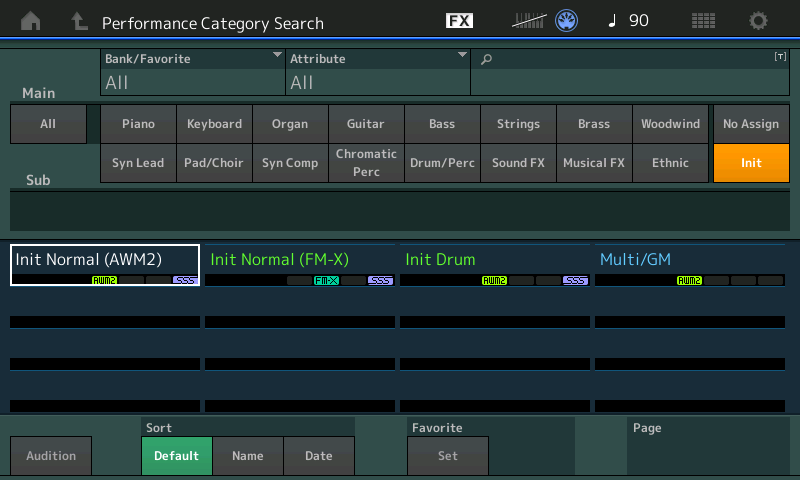

The V3 Sound Yammex XXL module and its closely-related sister, the Grand Piano XXL module, have very good orchestral voices. The XXL modules are small and weigh only 0.5 pounds (1.2kg) each. Hmmm, I think we have a candidate here.

The other half of the rehearsal formula is a MIDI controller, of course. Fortunately, I have an Arturia Keylab Essential 49 in hand. The Arturia is a relatively compact 49-key controller with lots of pads (8), knobs (9) and sliders (9). The Keylab Essential 49 is a relatively light 6.6 pounds (3kg).

Seems like we should have a match…

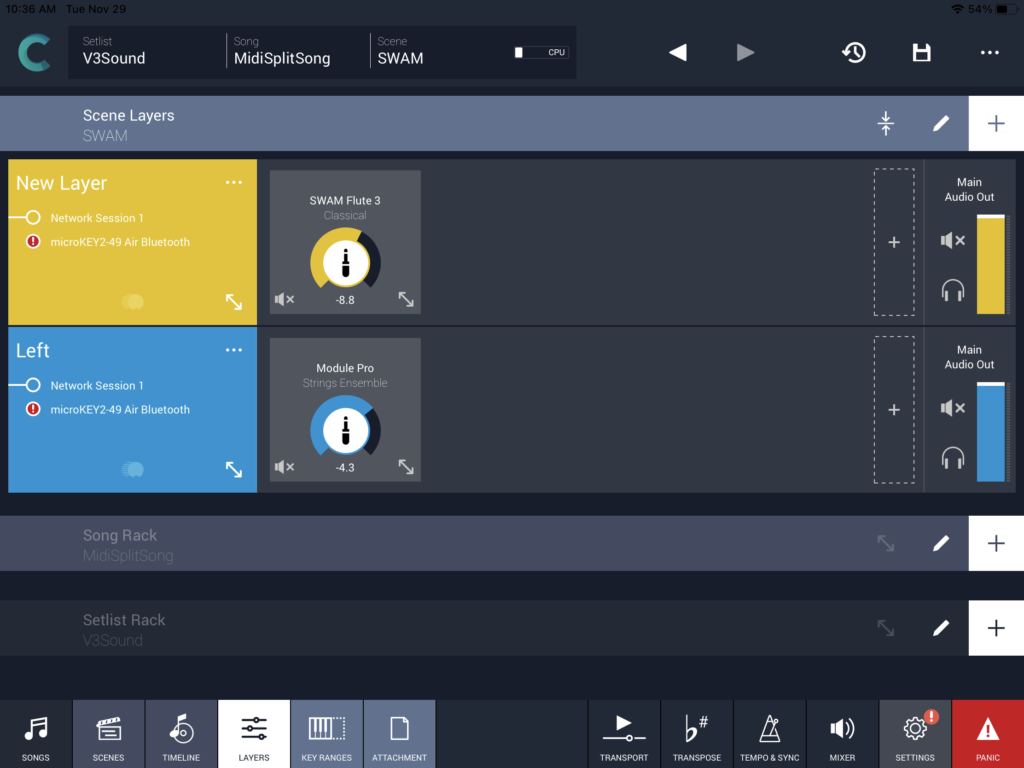

I usually split the keyboard into LOWER and UPPER zones somewhere around G3 (AKA G below middle C). This split gives my left hand enough room to roam and accommodates melody lines that dip below middle C. Although I keep the LOWER sound simple (i.e., one patch), I often layer the right hand. Most synthesized acoustic instruments need a little thickening and timbral shaping. Two UPPER layers are a minimum; three layers are sufficient, four is too many.

Seems like a slam dunk — MIDI the Keylab Essential into the Yammex, make a few configurations, and go. Unfortunately, neither the Keylab Essential or Yammex module support the split and layer capability that I need.

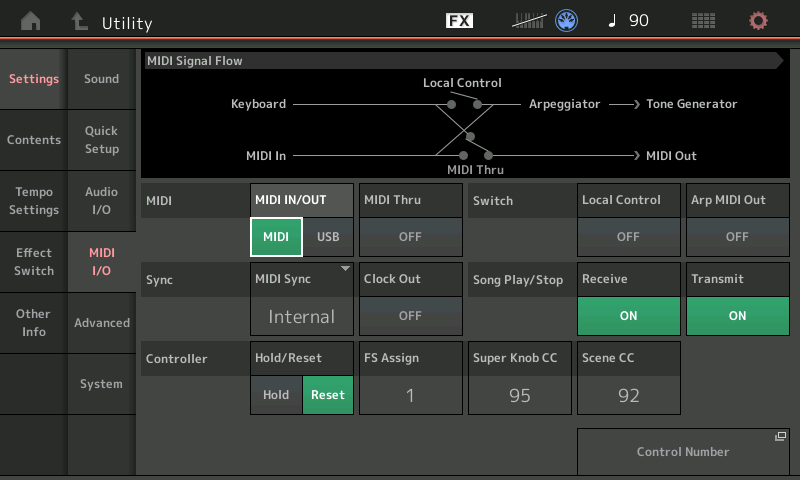

Time to rant about the stupidity of most MIDI keyboard controllers. Only a few 49-key controllers have split, layer, or zone capability: Samson Graphite 49, Nektar Panorama P4, Novation SL MKIII, Roland A-500. In the case of the Yammex module, the controller must send a full Bank Select MSB, Bank Select LSB, Program Change message sequence. Many controllers fail even this basic requirement.

The Arturia Keylab Essential, at the very least, sends a complete patch change message sequence. And, I am not going to buy yet another controller!

Enter the MIDI Solutions Event Processor Plus (EPP). The EPP is a MIDI-powered microcomputer that receives MIDI messages on 5-pin, modifies messages as determined by a set of rules, and sends the modified MIDI stream out through 5-pin. The Keylab Essential has a 5-pin MIDI OUT which is electrically compatible with the EPP. (The Keylab Essential voltage is about 4.5V as measured with a digital multimeter.) The EPP sits between the Keylab Essential MIDI OUT and the Yammex XXL MIDI IN. The EPP is itself a light-weight unit and adds negligible weight to the rig.

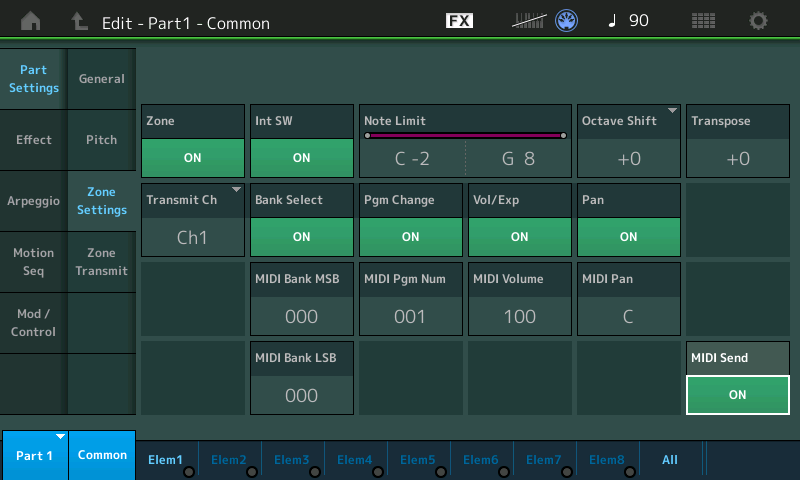

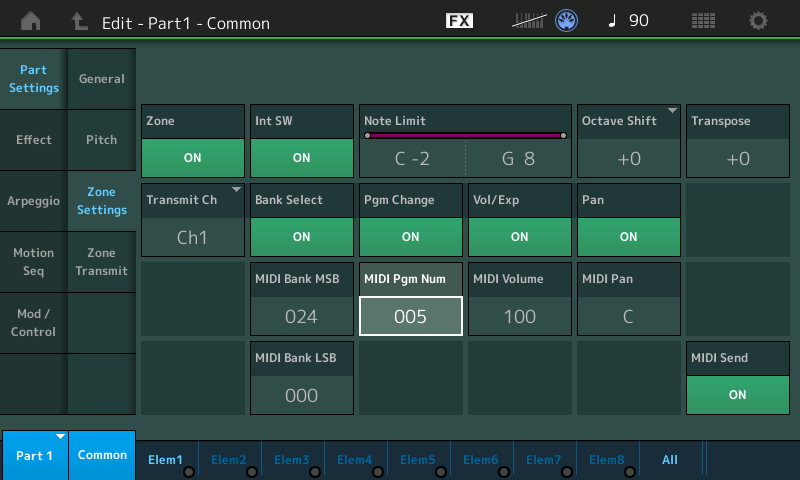

I programmed the EPP to split note ON/OFF messages arriving on Channel 1. Destination MIDI channel is determined by key zone: UPPER1 (Channel 1), UPPER2 (Channel 2), UPPER3 (Channel 3), LOWER (Channel 4),

- Channel 1 note ON/OFF at and above the split point are copied to outgoing Channels 1, 2 and 3.

- Channel 1 note ON/OFF below the split point are copied to outgoing Channel 4.

I also created rules to respond to button presses sending continuous controller 83 (CC#83). These rules initialize the four channels by sending patch change and expression (CC#11) messages. The EPP-based solution should work with any MIDI controller and multitimbral (multi-channel) module as long as MIDI communication is 5-pin.

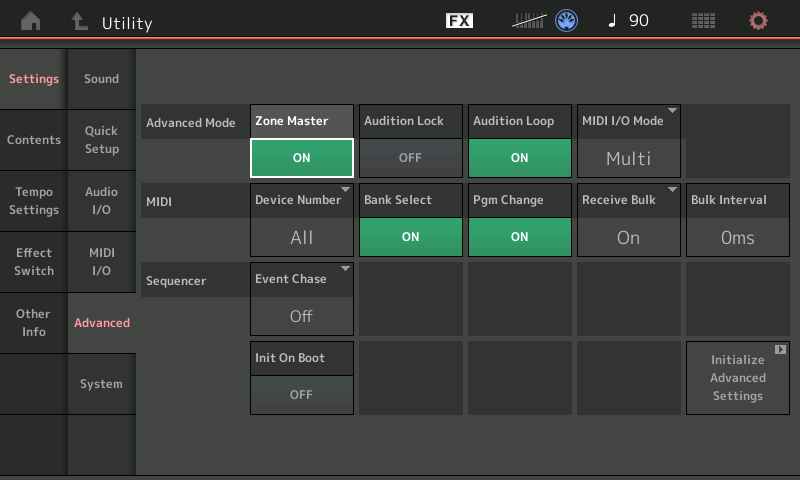

Early on, I auditioned the Yammex sound set and had identifed 15 or so favorite Yammex voices. The following four voices are assigned to Yammex channels 1 to 4 by the EPP when it receives CC#83:

- Channel 1: 63 / 116 / 7 Full Strings 2 Long

- Channel 2: 63 / 118 / 58 Flute EQ

- Channel 3: 63 / 117 / 49 Classic Horn Ensemble

- Channel 4: 63 / 116 / 7 Full Strings 2 Long

The idea is to use Channel 1 as the main solo voice and Channels 2 and 3 as optional orchestral coloring. Flute EQ and Classic Horn Ensemble are mellow, unobtrusive and mix well with other voices. Channel 4, of course, is the left hand.

Initially, Channels 1 (UPPER1) and 4 (LOWER) are assigned an ensemble string voice, a reasonable default. Expression values are set such that strings are heard, and Channels 2 (UPPER2) and 3 (UPPER3) are silent.

Voices are assigned in the following way to the eight Keylab Essential pads:

Violin Oboe Flute Eng Horn

63 / 116 / 22 63 / 118 / 48 63 / 118 / 57 63 / 118 / 49

Full Strings 2 Cello Flugelhorn Bassoon

63 / 116 / 7 63 / 116 / 24 63 / 117 / 15 63 / 118 / 50

Normally, these are the main solo voices to be assigned to UPPER1 (Channel 1). However, using Arturia’s USER MIDI channel feature, these voices can be assigned to UPPER2 (Channel 2), UPPER3 (Channel 3) and LOWER (Channel 4), too. That allows for a lot of game-time flexibility!

Wait, there’s more. I assigned MIDI expression to Sliders 5 through 8:

- Slider 5: UPPER1 (Channel 1) expression/level

- Slider 6: UPPER2 (Channel 2) expression/level

- Slider 7: UPPER3 (Channel 3) expression/level

- Slider 8: LOWER (Channel 4) expression/level

The sliders let me mix voices dynamically. A voice is silenced when I pull its Slider all the way down.

The table below summarizes the Keylab Essential knob, slider, pad and button MIDI assignments:

Knob #1 Cutoff CC#74 Brightness

Knob #2 Resonance CC#71 Timbre

Knob #3 Vib Rate CC#76 Vibrato rate

Knob #4 Vib Depth CC#77 Vibrato depth

Knob #5 Vib Delay CC#78 Vibrato delay

Knob #6 Port Time CC#05 Portamento time

Knob #7 Chorus CC#93 Chorus level

Knob #8 Reverb CC#71 Reverb level

Knob #9 CC#17 free

Slider #1 Attack CC#73 Attack time

Slider #2 Decay CC#75 Decay time

Slider #3 Sustain CC#64 Sustain

Slider #4 Release CC#72 Release time

Slider #5 UPPER1 CC#11 Expression channel 1 Solo

Slider #6 UPPER2 CC#11 Expression channel 2 Flute EQ

Slider #7 UPPER3 CC#11 Expression channel 3 Classic Horn Ens

Slider #8 LOWER CC#11 Expression channel 4 Strings

Slider #9 CC#85 free

Pad #1 63 / 116 / 22 Violin

Pad #2 63 / 118 / 48 Oboe

Pad #3 63 / 118 / 57 Flute

Pad #4 63 / 118 / 49 English Horn

Pad #5 63 / 116 / 7 Full Strings 2 Long

Pad #6 63 / 116 / 24 Cello

Pad #7 63 / 117 / 15 Flugelhorn

Pad #8 63 / 118 / 50 Bassoon

Button #1 (Part1) CC#65 Portamento ON/OFF (toggle)

Button #2 (Part2) CC#82 Momentary (Generic ON/OFF)

Button #3 (Live) CC#83 Initialize voices (Momentary)

So far, I’m having fun mixing and matching voices on the fly and trying new timbral combinations. One drawback is having to carry around a mental map to find, select and mix voices. I wish there was a way to display the current voice assignments! I plan to add stickies to the Keylab Essential to assist navigation and reduce pilot workload.

I hope this article has sparked ideas for your own control set-ups. The general principles should apply to most MIDI keyboard controllers and multi-timbral tone modules.

Copyright © 2022 Paul J. Drongowski