I thought, “When it comes time to test the 5-pin MIDI interface with the littleBits Arduino, just hook it up. Download the sketches. Take a victory lap.”

Instead, I got an “opportunity” to discover and learn. Not so fast, but not so bad, either.

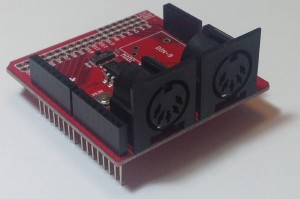

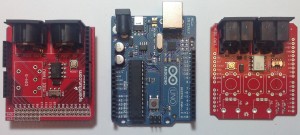

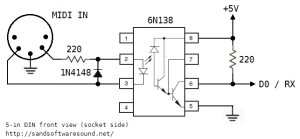

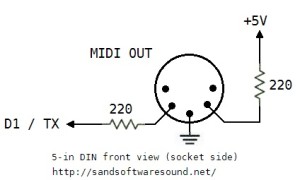

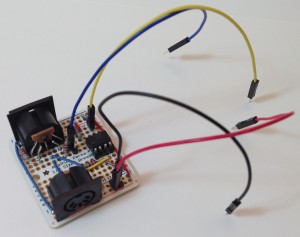

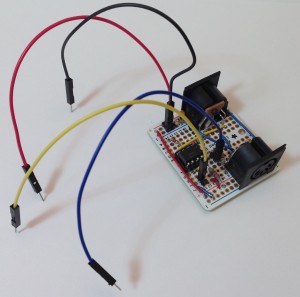

Please recall that a few posts ago I described the design of a 5-pin MIDI interface for Arduino. The MIDI IN part of the interface attaches to the Arduino RX pin (pin D0) and the MIDI OUT part connects to the TX pin (pin D1). I tested the 5-pin MIDI interface with an Arduino UNO board using the simple MIDI sequencer sketch and a sketch to echo MIDI IN to MIDI OUT. My original plan was to connect the 5-pin MIDI interface to the littleBits Arduino via two protoboards, then run the sketches, again, for testing.

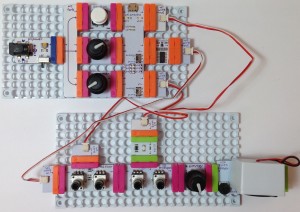

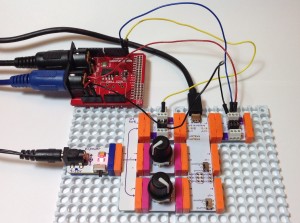

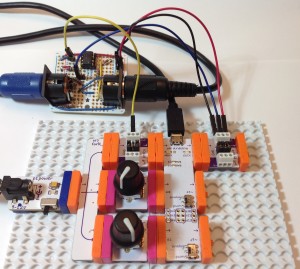

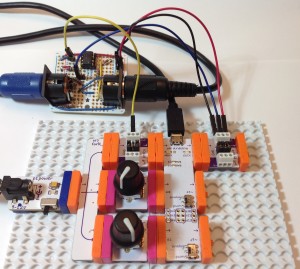

First, the hook up. The image below shows the littleBits hardware. (Click the image for full resolution.) The Arduino is “at the heart” and communicates with a PC through the USB port. The littleBits proto module directly to the left of the USB port brings the logic-level MIDI IN signal to the Arduino RX pin. The proto module directly to the right of the USB port sends the Arduino TX signal to the MIDI OUT circuit. The signals to and from the 5-pin MIDI interface board are:

- Yellow wire: Logic-level MIDI IN

- Blue wire: Logic-level MIDI OUT

- Red wire: +5 Volts (Vcc)

- Black wire: Ground

MIDI is a serial communication standard operating at a rate of 31,250 bits per second. RX and TX are the Arduino’s digital serial receive and transmit pins, respectively.

So far, so good. There are a few extra details to consider. The positive supply voltage (+5 Volts) and ground are distributed throughout the whole interface board. Only one set of power supply connections are needed to power the interface board. I attached the power supply connections to the proto module handing the MIDI OUT. Next, the proto module jumpers are configured a little bit differently on the MIDI IN and MIDI OUT sides. Having all three jumpers in place, the MIDI OUT proto module passes all signals: Vcc, ground and the data signal arriving from TX. The MIDI IN proto module only passes Vcc and ground. It does not pass the signal from its input bitSnap. The output from the proto module is generated by the signal coming from the 5-pin MIDI interface board (i.e., the yellow wire). This signal is send to the RX pin.

Adhering to my original test plan, I downloaded the simple MIDI sequencer sketch. This sketch tests the MIDI OUT circuit by sending MIDI note on and note off messages. I attached the MIDI OUT connector to a MIDI tone module, flipped the power switch, and no sound. MIDI data was not being sent to the MIDI tone module. After much wailing, gnashing of teeth and browsing, I remembered that the Arduino Leonardo board has two serial ports, not one port like the UNO. One serial interface handles RX/TX and another serial interface handles USB communications.

The littleBits Arduino is a Leonardo board. Was the MIDI data being sent to the USB port? I turned on the Serial Monitor in the IDE. Yep, the Serial Monitor was showing jibberish arriving from the Arduino. I expected jibberish because the bit rate was all wrong, but nonetheless, observations confirmed that MIDI data was going to the wrong port (USB instead of TX).

The Arduino IDE exposes two serial ports for a Leonardo board:

- “

Serial” refers to the virtual serial port over USB.

- “

Serial1” refers to the serial port through RX/TX.

Originally, I wrote and compiled the MIDI sequencer sketch for an Arduino UNO board. The calls to write() refered to Serial. That’s fine on the UNO because the UNO uses the same serial port for RX/TX and USB communication and everything works. On Leonardo (littleBits), however, the sketch refers to the USB serial port, not RX/TX as I had intended.

I solved the problem with conditional compilation. Here is the new code for the function MidiSend() in the MIDI sequencer sketch:

//

// Send a short, 3-byte MIDI message

//

void MidiSend(byte cmd, byte data1, byte data2)

{

#ifdef LEONARDO

Serial1.write(cmd | CHANNEL) ;

Serial1.write(data1) ;

Serial1.write(data2) ;

#else

Serial.write(cmd | CHANNEL) ;

Serial.write(data1) ;

Serial.write(data2) ;

#endif

}

The symbol “LEONARDO” determines the code to be compiled into the sketch. If LEONARDO is defined then the sketch sends MIDI bytes to Serial1. If LEONARDO is not defined, then the sketch sends MIDI bytes to Serial. I also needed to fix up the code in setup():

#ifdef LEONARDO

Serial1.begin(31250) ;

#else

Serial.begin(31250) ;

#endif

After making these changes and defining LEONARDO at the beginning of the sketch:

#define LEONARDO 1

I compiled and uploaded the sketch. Voila! I heard music from the tone module! MIDI data was now being sent to the appropriate Arduino serial port (TX).

Along the way, I also learned some useful information about the RX and TX LEDs. The RX and TX LEDs flash when data is transfered through the USB port. They do not flash when data is sent through the RX/TX pins. If you want to flash the LEDs yourself, then use the following macros:

RXLED0;

RXLED1;

TXLED0;

TXLED1;

These macros are a feature of the Leonard board and are not recognized on UNO.

Two separate, independent serial ports has its advantages. First, it isn’t necessary to disconnect the 5-pin MIDI interface board when uploading a sketch. With only one serial port on UNO, TX/RX and USB communication cannot peacefully co-exist. On Leonardo (littleBits), they do peacefully co-exist and you can use the virtual serial port over USB (i.e., Serial Monitor) to trace program execution and print debug messages while using RX/TX for MIDI communication. Finally, if we don’t ever touch Serial1, we should be able to configure D0 and D1 as regular Arduino digital input and output pins (respectively).

By now, you realize that I had to modify the sketch that echoes MIDI IN to MIDI OUT, too. Instead of conditional compilation, this sketches defines a symbolic constant, “SERIALPORT,” which expands to the name of the serial port to be read and written. Full disclosure: I did not test the MIDI library version on littleBits (Leonardo).

//

// Send MIDI IN to MIDI OUT (THRU)

//

// Author: P.J. Drongowski

// Date: 6 June 2016

// Version: 1.1

//

// Copyright (c) 2016 Paul J. Drongowski

// Permission granted to use, copy and distribute

// Uncomment the following line to use the Arduino

// MIDI library instead of serial read() and Write().

// #define USE_MIDI_LIBRARY 1

// This has not been tested/debugged on LEONARDO!

// Define the symbol SERIALPORT to select the appropriate

// serial port:

// Serial UNO

// Serial1 LEONARDO/littleBits

#define SERIALPORT Serial1

#ifdef USE_MIDI_LIBRARY

#include <MIDI.h>

MIDI_CREATE_DEFAULT_INSTANCE() ;

void setup() {

MIDI.begin(MIDI_CHANNEL_OMNI) ;

}

void loop() {

if (MIDI.read())

{

MIDI.send(MIDI.getType(),

MIDI.getData1(),

MIDI.getData2(),

MIDI.getChannel());

}

}

#else

int midiByte = 0 ;

void setup() {

// Initialize the serial port for MIDI

SERIALPORT.begin(31250) ;

}

void loop() {

if (SERIALPORT.available() > 0) {

midiByte = SERIALPORT.read() ;

SERIALPORT.write(midiByte) ;

}

}

#endif