The Raspberry Pi 2 Model B (RPi2) is a computational gem. For $40 USD, you get a 900MHz quad-core ARM processor, a built-in graphics core, 1GBytes of RAM, 4 USB ports, HDMI, an Ethernet port, audio output and a Micro SD card slot. (The RPi2 does not have a built-in audio input.) This platform can handle most of the every-day tasks that people can sling at it and could easily replace platforms costing 10 times as much. Add in the cost of a keyboard/mouse, display and Micro SD card, and the total package price tips the scale at a little over $100.

When the RPi2 was introduced in February 2015, the Raspberry Pi Foundation released Raspsian Wheezy, the first Linux distribution supporting the RPi2. I installed the first release last February, and it felt, well, kind of wheezy.

I just installed the latest release, Raspbian Jessie (February 2016) and all I can say is “Wow.” This release feels finished. If you tried Raspbian on RPi2 before and were disappointed, it’s time to come back into the fold. (Download Raspbian.) This is the release that should have been there at the RPi2 launch! (See a quick introduction to the Jessie desktop.)

With a foot of snow on the ground, it seems like an opportune time to see what RPi2 and Jessie can do for musicians. I intend to try the RPi2 as a synthesizer and will post my experiences here. In the meantime, here are some tips for getting started with RPi2 and Jessie.

Linux requires just a little more work to get started than Mac OS X or Windows. However, if you put in just 10 or 20 minutes, you can have a quad-core music making machine for cheap. Shucks, even OS X and Windows 7 need to know your account name, etc. and Jessie doesn’t require much more information than that. So, what follows is my personal checklist for getting started with Raspberry Pi 2.

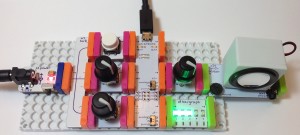

Hardware

Of course, you need the hardware. I bought a Canakit Raspberry Pi 2 kit last year. The Canakit includes most of the accessories that you need to get started. I imagine that future Canakit’s will include the latest Raspbian release (Jessie) pre-installed on Micro SD card.

My RPi2 lives in a cheap plastic case. That’s good enough — no fans, no heatsinks. I use an old HP monitor with an HDMI input and an even older Logitech wireless keyboard and mouse. The Logitech wireless interface takes up a single USB port, leaving three open USB ports. I connect the RPi2 Ethernet port directly to our router since I like to have the network up and running right from the start. The Canakit package included a USB Wi-Fi interface, but I never felt motivated to bring it up. Cables work good, too.

Once you have everything connected, it’s time to move on to software.

Download and install

Since our house is littered with computers, I first downloaded Raspbian Jessie to a Windows 7 PC. I followed the installation guide for Windows and wrote the disk image to an 8GByte Micro SD card. I do not recommend using anything smaller than an 8GByte card since you will need room for all the applications, samples and stuff for your projects.

The installation guide recommends the Win32DiskImager utility from Sourceforge. This utility works like a champ. Just be sure that you write to the correct destination disk!

If you’re installing from Linux or Mac OS X, there are installation guides for you, too. I do not recommend upgrading an old Wheezy system to Jessie. I read through the process and it is far easier to do a clean install.

First and second boot

Plug the Micro SD card into the RPi2 and apply power (i.e., plug in the power supply). It takes a few moments until the RPi2 boots the kernel (AKA “the OS”) and starts the X Windows system. The stock RPi2 boots into the desktop. The default user name is “pi” and the default password is “raspberry”.

At this point, it’s important to get a few housekeeping tasks out of the way. These tasks are similar to the ones you need to perform after installing OS X or Windows. These tasks use the raspi-config utility.

First, launch a terminal window by clicking on the terminal window icon in the task bar at the top of the screen. This action brings up a textual “shell” where you enter commands. Enter:

sudo raspi-config

to launch the raspi-config utility. The sudo tells Linux that you want to use administrator (“super user”) privileges when running raspi-config. Linux will prompt for a password. Enter “raspberry”, the default password for the default user, “pi”.

raspi-config displays a rather 70s-ish interface with several options. Use the arrow keys to move between items. Use the ENTER key to select an item.

The disk image which you wrote to the Micro SD card probably didn’t use all of the available space on the card. So, your first job is to extend the Linux file system to use the entire Micro SD card. Use the arrow keys to move to the “Expand filesystem” item. Hit ENTER. When prompted to reboot, choose OK. You need to reboot to get access to the full capacity of the Micro SD card.

After reboot, you should be back in the desktop again. Launch a terminal window to get the shell. Enter sudo raspi-config to perform a few more housekeeping steps related to internationalisation. Use the arrow keys to move to the “Internationalisation options” item and hit ENTER.

It’s called “Internationalisation,” but it’s really configuring your RPi2 to your local country or region. raspi-config displays a short list of options. Choose the “Change timezone” option, follow the on-screen directions, and set your local timezone.

Next, choose your locale. The locale controls language and formating of date, time, currency, etc. The default locale is set for Great Britain. If you’re in the United States, for example, select one or more locales for the US, e.g., “en_US.UTF-8 UTF-8”. The text interface is a little weird here — use the SPACE key to mark one or more locales and hit ENTER when finished.

Then, change the keyboard layout. Follow the on-screen directions to find a close match for the keyboard that is connected to your RPi2. When you see questions about “compose key,” etc., fake your way through the menus. You probably won’t be doing this stuff anyway.

Finally, reboot. Rebooting the system at this point makes sure that the locale and other internationalization changes kick in.

Explore and browse

After reboot, the RPi2 should again return to the desktop. Now it’s time to explore the desktop a little bit. I recommend taking a tour through the start menu in the upper left corner of the desktop. When you find a menu item for the browser, try it out! If all is good with your network connection, then you should be able to access the Web. This is my lifeline to helpful information about Raspbian Linux and the many tutorials and HOW-TOs on the Web.

Also, check out the File Manager. This is a graphical way to browse through your files. Linux uses a hierarchical file system where absolute path names begin from the root, which is symbolized by the slash (“/”) character. More about this in a minute.

Just a few more things

I recommend creating a new user for yourself and keep the default user “pi” around for emergencies or administration. The Raspberry Pi folks have a nice introduction to user management. It’s a short read and now that you have the browser running, why not?

If you’re too lazy to read the guide, then use the following command to create a new user:

sudo adduser XXX

where “XXX” is the name of the new user. The system prompts for the new user’s password. This part is up to you! You can remove the password for a user by entering the command:

sudo passwd XXX -d

where “XXX” is the name of the user. The passwd command can be used to change your own password, too. If you want to remove a user, then run the command:

sudo userdel -r XXX

where “XXX” is the name of the user to be removed.

The guide to user management describes “sudoers” and how to grant permission to a user to execute the sudo command. This process changes an internal user privileges file, so you must be careful. Enter the command:

sudo visudo

and find the line:

root ALL=(ALL:ALL) ALL

Create a new line using this line as a model, except replace “root” with the name of the user who is to be a new sudoer, e.g.,

XXX ALL=(ALL:ALL) ALL

Save the changes and exit the editor. Oh, the editor here is nano, which is one of the pre-installed applications.

Users have their homes in the directory “/home”. If the user’s name is “XXX”, then their home directory is named “/home/XXX”. Here are a few commands that you can use to navigate through the file system via the shell.

ls List directory

cd Change the working directory

pwd Display the current working directory

mkdir Make new directory

rmdir Remove directory

cp Copy file (or directory)

mv Rename a file (or directory)

rm Remove file

cat Display file contents

more Display file contents

nano Edit text file

date Displays the current date

If you need help, you can always enter the desired command with the “–help” option. Or, you can display the manual page for the command, e.g., “man ls”. All of these commands have many options, making them quite flexible and powerful.

You can find more basic information about using Linux on this page.

Install applications

Speaking of new applications, you can install a new application from the command line if you know the package name. This is the most straightforward way to install a package (application). For example, I like the emacs text editor. The following command installs emacs:

sudo apt-get install emacs

The apt-get command searches for the package on-line, downloads it and installs it. The command also installs any other packages which the target package needs (e.g., libraries). In Linux terms, it resolves dependencies. Installation is sometimes slow, so please be patient.

There is also a package manager with a nice user interface. Find the package manager in the desktop start menu and browse through the available applications. I’ll revisit this subject in future posts when we discuss specific music-oriented applications.

USB flash drives

The need for a USB flash drive is sure to come up. I recommend this guide to adding and using USB drives. Here are a few quick commands for reference. Create a mount point:

sudo mkdir /mnt/usb_flash

Mount the USB flash drive (after inserting the drive):

sudo mount -o uid=XXX,gid=XXX /dev/sda1 /mnt/usb_flash

where XXX is your user name. Unmount the flash drive when you’re finished using it:

sudo umount /mnt/usr_flash

You can display the currently mounted file systems with the command:

df -h

This command also shows the amount of used and available space in the various file systems and drives.

Raspbian Jessie is smart enough to recognize when a USB drive is inserted. It displays the File Manager automatically. If you are a File Manager type of person, definitely go this route. You must eject (unmount) the drive before removing it. The EJECT button appears in the upper right hand corner of the desktop.

Boot to a login shell

Raspbian Jessie boots into the desktop as the default user “pi”. You probably want to boot into your own account instead. At the moment, you need to dig into some system files to make the change and I simply don’t recommend diving into that, especially if you are new to Linux.

Instead, you can easily change the boot behavior using raspi-config. Launch raspi-config and choose the “Enable Boot To Desktop” option. Then, choose to boot to the command line. The next time you boot, the system will display a login prompt where you can enter your user name and password. Once your identity is validated, Linux puts you directly into a command line shell. If you want to, you can enter any Linux command into the shell and do some work. When you want to start the X Windows system and the desktop, just type:

startx

Read the on-line documentation about respi-config for more information.

Shutting down

All operating systems like to shut down in an orderly way. OSes often times keep data in temporary buffers that need to be flushed to disk or flash memory. An orderly shutdown helps keep data in a consistent, correct state.

You can shutdown the system through the desktop start menu. (Yeah, that sounds oxymoronic.) You can also shutdown the system via the command line shell. Just execute the command:

sudo shutdown -h now

The -h option asks Linux to halt the processor after shutting down. The shutdown command has other options for rebooting and so forth:

sudo shutdown -r now

Here’s another way to force a reboot. Just enter:

sudo reboot

on the command line.

If you enjoyed this introduction, you might want to check out the Raspberry Pi tips and tricks page that I wrote for the first generation Pi.

Well, that wasn’t so bad, was it? Good luck and have fun with Raspberry Pi 2!

All site content is Copyright © Paul J. Drongowski unless otherwise indicated.